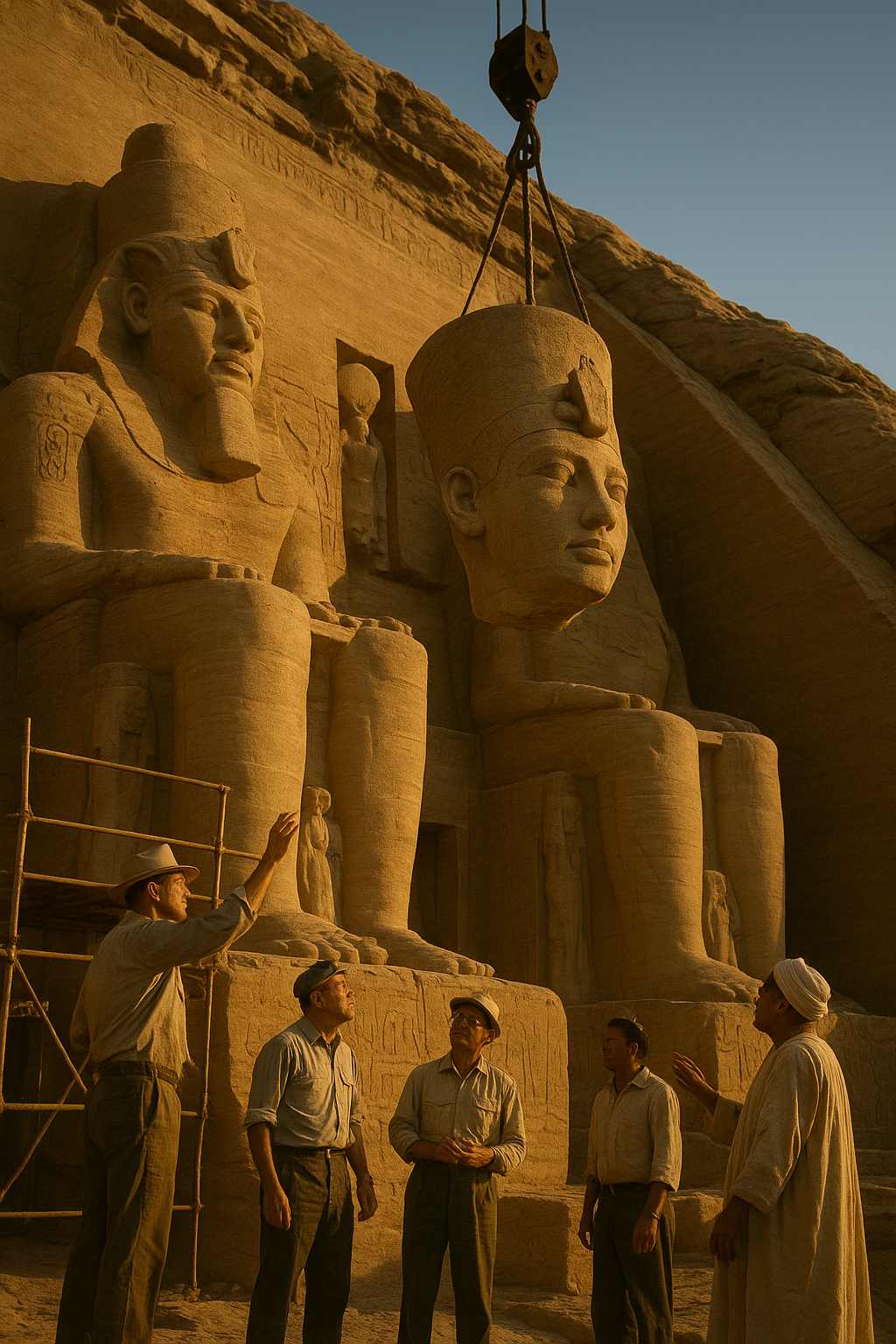

Featured Image above – Engineers and workers carefully moving Queen Nefertari’s head at Abu Simbel during the 1960s temple relocation.

He loved her like a god — carving her face into temples, aligning the sun to kiss their statues, and ensuring her gaze never left him.

Ramses II was now a god-king walking in a shadow of his own making.

He had ridden out from Tjaru and fought the Hittites to a stalemate at Kadesh and spun it into a masterpiece of propaganda. He commanded two versions of the event to be carved in stone: a thrilling, first-person Poem that cast him as a lone hero saved by the god Amun, and an official Bulletin that presented the story as military fact. Together, they were a potent magic, designed to convince both the heart and the mind for all eternity., carving his “victory” on every temple from Abu Simbel to the Ramesseum.

Part I of this story is here Ramses II & Nefertari: Legacy, Love, and the Pharaoh Who Carved for Eternity

He had signed a lasting peace treaty, marrying a Hittite princess, Maathorneferure, in a move of political genius that secured his borders.

He had built and built and built: the completed Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, where his deeper, more prominent cartouches overshadowed his father’s finer work; the Ramesseum, his vast mortuary temple where a colossal statue of him, now known as Ozymandias, would one day lie shattered; his additions at Luxor Temple and he had completed his father’s monument to Osiris, the Temple at Abydos, where, as a boy, he had watched his father’s discussions with architects and craftsmen, pouring for endless hours over papyrus drawings with artists, commissioning the building of the seven chapels and the second court.

Ramses had finished his father’s grand design by placing him among the gods and declaring for all to see how beloved of the gods, Seti had been – anointed and blessed for all eternity by Horus and Thoth – gods of courage, strength and wisdom.

Years turned into decades. He outlived Nefertari by over forty years. He outlived his beloved mother, Tuya, for whom he built a chapel at the Ramesseum. He outlived his crown prince, Amunherkhepeshef, and many other children. His long reign was one of stability and unmatched glory, but it was also a long, slow procession of loss.

He finally passed the crown to his thirteenth son, Merneptah, a man in his sixties, seasoned and steady, who would soon face invasions that would have broken a lesser king.

Walk through his temples today. Feel the sun where his likeness once stared out. You are not walking among ruins. You are walking inside the mind of a king. Run your fingers over the hieroglyphs at Abu Simbel or Karnak or Abydos. Feel the depth of his cartouches, carved deeper than any pharaoh’s before or since. It was a literal, physical act of ensuring his name—his very essence—would not be erased by time. Know that his fingers touched every stone because you can be sure his essence is in the stones. You are reading a story he desperately wanted you to believe. A story of battle, love, divinity, and power. It is a magnificent story, gripping and grand.

And it is a powerful reminder that history is rarely a simple record of what happened. It is often the breathtaking, enduring, and utterly human art of what someone needed us to remember.

Last updated on 20/12/2025 by Marie Vaughan