The air at Tjaru was the breath of Set, the god of chaos—a searing, gritty roar that scoured the massive fortress walls, laden with the fine, white dust of Sinai. This was the Tjemet, the “Wall of the Ruler,” the most formidable clenched fist in the arsenal of Pharaohs Sety I and now his son, Ramses II. It was the gateway, the barrier, the defining line between Ma’at and Isfet—cosmic order and the consuming void.

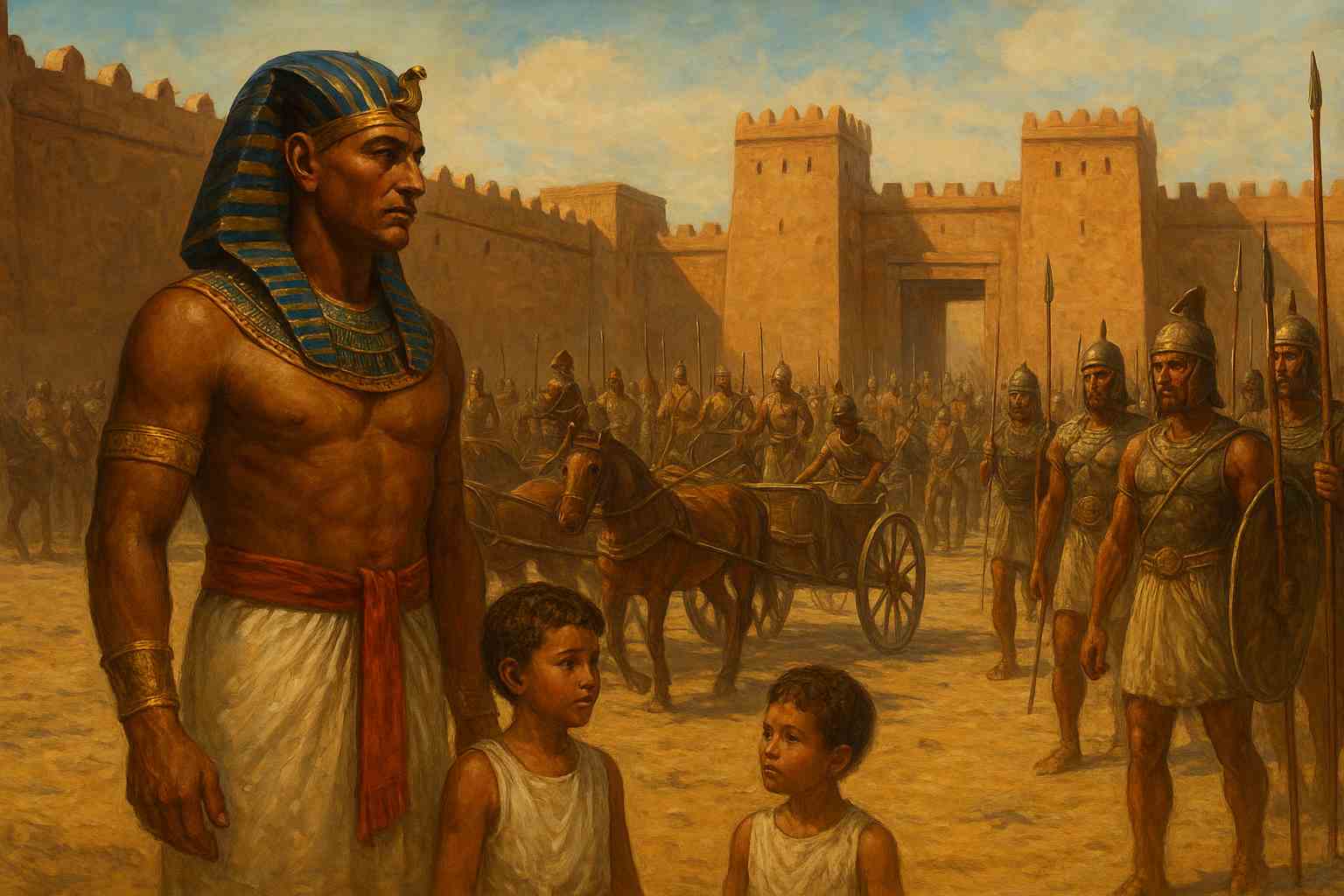

To stand on the ramparts in the age of the Ramessides was to feel the pulse of an empire. And on this day, the heart of that empire beat in the central courtyard, where a figure in a linen kilt, his body coiled with the energy of a man who knows his destiny, inspected the ranks. This was Usermaatre Setepenre—Ramses II. The air, thick with the scents of sun-baked clay, oiled leather, and the sweat of Nubian conscripts, seemed to still around him.

He was not alone. Beside him, trying to mimic their father’s stern posture, were his young sons. Amun-her-khepeshef, the eldest, his eyes wide not with fear, but with the immense weight of being the crown prince going into battle. Pre-her-wenemef, his jaw set, no doubt rehearsing the stories of his grandfather Sety’s victories carved into the very walls around them. They were boys, yes, far from the comfortable palace and the arms of their mother, Nefertari, but here, at the edge of the world, they were being forged into men of the Ramesside line. This fortress was their classroom, and the coming war at Kadesh their final examination.

The fortress itself was a monument to this inheritance. The walls, thick as five men, were canvases of imperial propaganda. Great carved reliefs, freshly painted, depicted Sety I in his chariot, his mace smashing the heads of Libyan chieftains. Newer stones showed a young, vigorous Ramses II, his gaze fierce under the blue war crown, personally directing the fort’s expansion. For his sons, these were not just stories; they were a standard to be met.

This was the launch point of the Warrior Kings. The garrison here was not just a defense; it was the tip of the spear aimed directly north. In the vast courtyards, the newest models of Egyptian chariots—lighter and faster than their Hittite counterparts, built for the new art of mobile archery—stood in perfect rows. Regiments of the Sherden, fierce sea-peoples now loyal to Pharaoh, their horned helmets distinctive, drilled under the punishing sun. The glint was not just of bronze, but of the finest Khepesh blades, their curved edges hungry for the flesh of Hittites. It was a sight for the young princes to absorb: the terrifying, beautiful machinery of their father’s power.

The sounds were a symphony of empire-building. By day, the air thrummed with industry: the crack of whips driving Canaanite slaves to quarry stone, the shouts of engineers overseeing the digging of yet another well, the rhythmic tramp of the Pre-aa’s personal troops, the Menfyt, marching out on patrol. At night, a different sound emerged—the low murmur of soldiers from a dozen different lands sharing stories, the clink of a sentry’s scale armor as he paced the fire-lit walls, his eyes scanning the northern darkness from which the Hittite threat would come.

Tjaru was no longer just a shield. Under Ramses II, with his heirs at his side, it was a springboard. It was the last taste of home for an army marching to a glory that would echo for millennia and the first, brutal welcome for prisoners dragged back in chains. It was the embodiment of a new, aggressive Egypt—a kingdom that no longer merely defended its borders but actively projected its power. And from this grim, dust-choked fortress, the will of a Pharaoh and the future of his bloodline reached out to grasp a world waiting to be subdued.

The story of Ramses II is etched into the very stone of Egypt. To walk in his footsteps is to understand the ambition of the pharaohs. For those drawn to this history, our pages on transformative travel offer deeper context, and our curated Tours & Experiences can bring you to the lands he once ruled.

Last updated on 20/12/2025 by Marie Vaughan