1. Touching Time: A Stone That Remembers

It is not merely a slab of grey-green siltstone. The Narmer Palette, holds the memory of desert nights and the echo of intentions set in stone. Imagine brushing your fingers over its carved surface and sensing the heat of a moment that changed the world. The Narmer Palette is one of Egypt’s most precious artifacts. Unlike Tutankhamun’s mask, it has never left the country. On the face of it a palette such as this was used for mixing cosmetics and in the Narmer Palette the cosmetics would have been mixed in the circular space made on the reverse side, by the intertwining of the two serpopards’ heads. However, I doubt the Narmer Palette was ever used for such a purpose. Yes, the Narmer Palette was a tool but not for blending cosmetics but for carrying and binding with Heka, the vision and intention of Narmer.

2. The Urge to Leave a Mark

To understand its power, we must step back. When did we first feel the urge to carve our story into the very bones of the earth? Long before Narmer, our ancestors painted dreams of hunts and spirits deep in cave sanctuaries. They scratched symbols onto stone with ochre. This is a human constant: the desperate, beautiful need to say, “I was here. This happened.” The Narmer Palette is a pinnacle of this ancient urge, not its beginning. It is the moment this impulse was harnessed with breathtaking sophistication not just to record, but to create reality. This is where a story became a country.

Ancient Intentions, Modern Law of Attraction

Using symbols and actions to influence reality was the essence of Heka. Today, we might call it manifestation, the Law of Attraction, or the subtle power of intention.

3. Narmer, the Man Behind the Stone

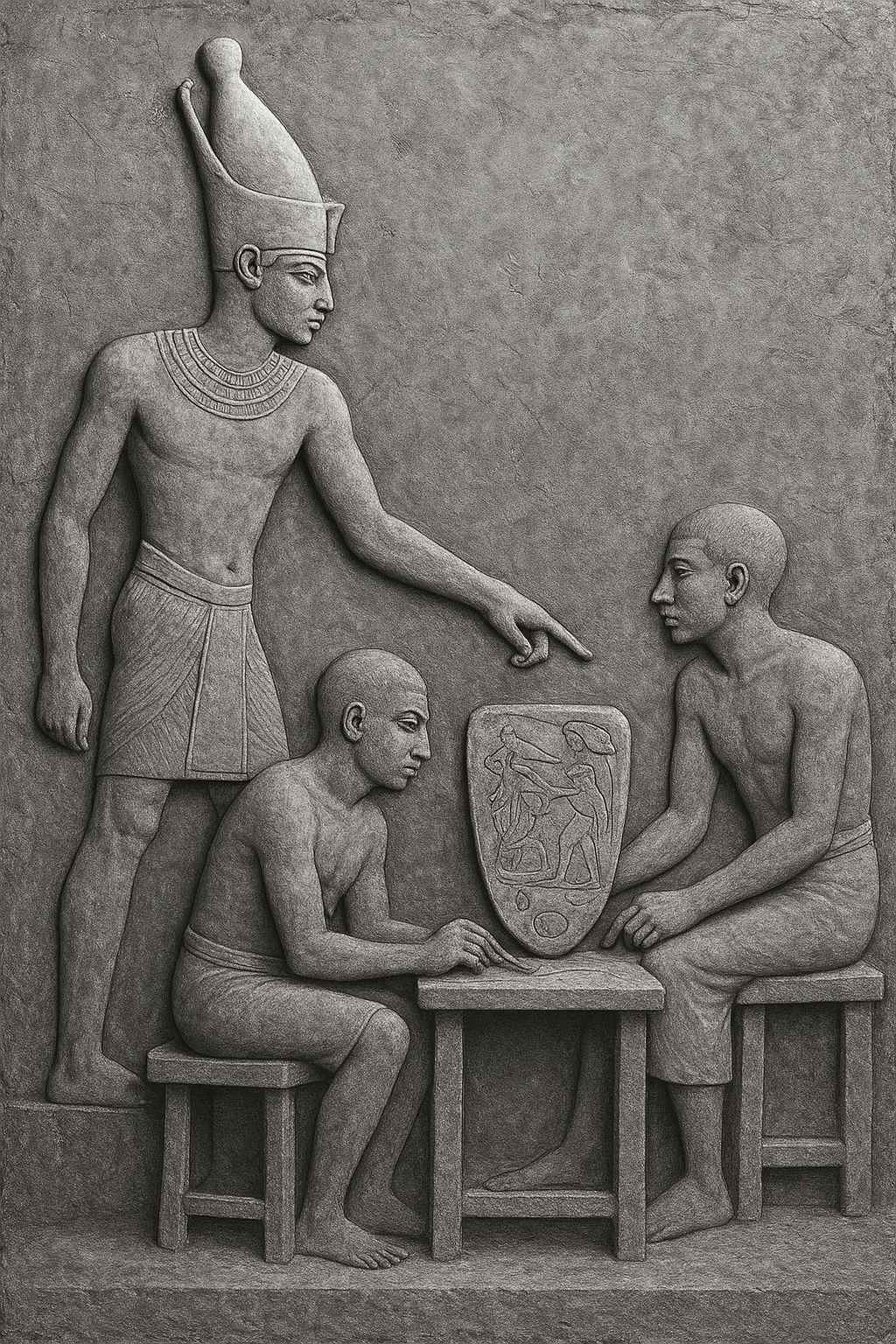

Imagine him not as a Pharaoh on a throne, but as a man with a powerful vision, Narmer. He is widely identified by Egyptologists as the first king of a unified Egypt, the founder of the 1st Dynasty, and this palette, dated to c. 3100 BCE, is a key piece of evidence. It is a ceremonial object, a votive piece for the gods, not a utilitarian item.

Look at the front. Here is Narmer, larger than life, the solid embodiment of power. He wears the crisp White Crown (Hedjet) of the South. He holds a mace, ready to strike a kneeling foe—a classic pose of royal power. Before him, the falcon god Horus, his divine counterpart, holds a rope tethered to the nose of a head that emerges from a papyrus clump—the symbol of the Nile Delta, the north. Horus subdues it, presenting it to the king. It is an act of terrifying, intimate possession. This is the moment the palette captures: not the brutal smash of battle, but the precise, divine moment of binding. Of connection. Behind him, his sandal-bearer anticipates the moment. Beneath his feet, two fallen enemies float in the abstract space of the conquered.

Now, turn it over. This is the revelation. Here, the same man, Narmer, now strides with purpose. But look at his head. He wears the Red Crown (Deshret) of the North. The message is staggering: I am both. I am all. He walks in a procession, reviewing the decapitated bodies of his foes, but the central image is one of creation, not destruction, of unification, binding and control – the control that Narmer has over the two lands of upper and lower Egypt. The central image is that of two serpopards—a leopard with a serpentine neck—its long neck coiled by attendants. Some Egyptologists see a symbol of controlled chaos; I see the forced, beautiful, and terrifying union of two opposing natures into one creature, just as Narmer was doing with the Two Lands. And in the bottom register, the great bull of the king demolishes the walls of a city.

Symbols of Power

The crowns, the falcon, the serpopard—they are not decorative. Each encodes authority, divine alignment, and the king’s mastery over both chaos and order. The heads of the goddess Hathor on both sides of the palette carries huge significance. Hathor was the goddess of healing, family, love, beauty, music but her alter ego was Sekhmet the goddess of destruction. The palette decrees that king Narmer has her protection when it comes to his intention to unify Egypt.

4. Heka: The Force of Creation

Heka is often mistranslated as simply “magic,” but in ancient Egypt, it was the operating system of the universe. Gods wielded it to bring the world into being. Humans used it through ritual, image, and speech. To speak something with true intention was to perform it, to make it real in the spiritual and physical realms. The wedjat amulet, for example, was not mere decoration; through Heka, it became protection. Heka was also divine, reminding all that creation belonged to the king.

“A word, a gesture, a carved image could make reality bend.”

5. The Palette as Ritual Tool

Now, look at Narmer’s palette not as a tool or mere curiosity, but as a tool of supreme Heka. This was a sacred, ritual object. By having his vision masterfully carved into enduring stone, Narmer wasn’t just describing a future victory. He was performing it. He was cementing it into the cosmic order (Maat). He was using the ultimate power of the image and the symbolic deed to imbue the consciousness of his people, both friend and foe, with an undeniable truth: There is no longer a North and a South. There is only Egypt, and I am its living embodiment. He was speaking a nation into existence. Read Heka: The Ancient Egyptian Magic That Still Shapes How We See, Behave, and Believe

Heka and the Law of Attraction

Just as modern manifestation relies on focused intention, Narmer used imagery and ritual to align minds and hearts with his will, creating reality through story and symbol.

6. The Discovery: Nekhen

The palette was discovered in 1897–1898 by Quibell and Green in the temple precinct of Horus at Nekhen (Hierakonpolis), north of Edfu. Nekhen was no backwater. It was the ancient, powerful capital of the Pre-dynastic kings of Upper Egypt, the heartland of the early culture that birthed the pharaonic state. The palette was found as part of a vast deposit of other revered ceremonial objects—like the Narmer Macehead—ritually buried in the sacred ground of the very temple of the god, Horus, who is shown supporting the king in the palette. It had served its purpose for a generation or two, shaping the mind of the new state, and then, having done its work, it was retired with honor, consigned to the earth within the god’s own house. It was not meant for the daily view of the common people, but for the eyes of the gods, the priesthood, and the elite—the very architects of the new state

👉 Explore all my transformative travel stories from Egypt

7. Why It Still Speaks

It worked so well that its truth echoes over 5,000 years later. We are still reading its message, still feeling the weight of its intention. That is the ultimate power of the word and image made stone. It’s a story that gets under your skin. It’s not about dates and kings. It’s about the power of a story, told with such intention and artistry that it can change the world. It’s the same power you feel standing in the shadow of our own Luxor temples—the sense that you are walking through a dream that was first carved into stone. Next time you walk through an ancient temple – especially an Egyptian one, never mind if the guide is telling you all the representations on the temple walls and the tombs are commemorative – keep your eyes open for the ones that speak to you of the Pharaohs’ Heka.

Last updated on 20/12/2025 by Marie Vaughan