Featured Image above: The day after her wedding at Philae, Leanne walks among the colossal Abu Simbel temples, immersed in the love story of Ramses and Nefertari — a moment where personal celebration meets ancient romance.

The Dust of Tjaru — A Pharaoh in Training

The air at Tjaru was a fine, gritted thing. It tasted of ambition—of sweat, leather, and the dust kicked up by ten thousand marching men. For a boy of 14, this was not a hardship. It was the only air worth breathing.

The boy was Ramses II. And the man he watched, a whirlwind of muscle and will, was not just his father. He was Pharaoh Seti I, the one who had mended a fractured Egypt. The Pharaoh’s voice, when it came, was low, meant for his son alone.

“Remember this, my son,” Seti’s voice was a low rumble, like the wheels of a thousand distant chariots. He gestured east, towards the lands of Canaan and the fierce Hittite empire. “A Pharaoh’s legacy is not written on papyrus. It is carved into the very land. It is measured in the fear of our enemies and the awe of our people.” His hand, calloused and strong, gripped Ramesses’s shoulder. “They forgot us under the weak and the heretic (Akhenaten). They will learn again to remember the name of Egypt. They will learn to remember us.”

Rameses swallowed, the weight of expectation a heavier armor than any he would ever wear. His grandfather, Ramesses I, had been a general who stumbled onto the throne. His father was a restorer, a warrior-king. What would he be? The question was a constant, silent companion.

Abydos: Where Memory and Stone Collide

That companion grew louder years later, as he stood, at the age of 22 with his father before the rising walls of the temple at Abydos. The sacred city of Osiris hummed with a different energy. Not the chaos of war, but the focused intensity of creation. The sound of a thousand chisels was a symphony of immortality

Seti placed a hand on a freshly carved block. It was part of the King List, a procession of cartouches stretching back to the dawn of time. Ramesses’s eyes traced the names of the great ones—Menes, Khufu, Amenhotep III. His father’s finger, however, paused over a patch of smoothed-over stone, a ghost in the narrative. A name had been erased.

“See, Rameses?” Seti’s voice was quieter now, aged by years of relentless campaign. “anyone can be erased. The sand, time, envy… they all conspire to cover a man’s name. Our only answer is to build so big, so brilliantly, that the sand itself cannot bury us. We must make ourselves indispensable to eternity.” He turned, his eyes holding the fire of a zealot. “Promise me. Promise me you will make them remember!” 3 short years later when Sety passed away and Ramses recalled that last time he accompanied Sety to Abydos, he wondered if his father had known then that he was running out of time himself. Was that why he had gone over and over the drawings for the temple with him? Had Sety known then that he would not finish the temple himself?

and you… wander the halls of Abydos when you can – look up at the carved hieroglyphs resembling the helicopter, stealth fighter and submarine and wonder… how much did Seti really know?

Ramses knew that Abydos held a special place in his father’s heart – it was only in looking back that Ramses realised that while there was a strong bond of love between himself and his father, he did not actually know the man himself, very well, if at all, and Abydos was a sacred place that their predecessors had spent little or no time and money on – until Seti remembered it.

Seti’s words branded themselves on Ramesses’s soul. Grief would come later, when Seti died. But first came a vow, hotter than grief: a vow of glorious, world-drowning one-upmanship and a decision to build better and bigger than anyone ever had.

The Shadow of Akhenaten: Lessons of Faith and Power

Seti and his son could not forget Akhenaten’s heresy: a near-erasure of Egypt’s gods and monuments. The boy saw how his father restored temples, rites, and authority, rebuilding Egypt’s spiritual heart while cautioning him against fanaticism. Ramses grew to understand that a king’s duty was both divine and human: to honor the gods, protect the people, and ensure the dynasty endured.

Crown Prince at Fourteen — Duty Meets Desire

At the age of 14 when Seti I named his son Ramses II, the Crown Prince, he bestowed upon him the ultimate tool of dynasty: a royal harem. This was not merely a luxury; it was a political engine, designed to secure the bloodline and forge alliances. Among these women was Isetnofret, older than Ramses, a choice steeped in strategy. Her potential lineage, perhaps tracing back to the pharaoh Horemheb, was a living tether to the previous royal house, a move to legitimize and solidify the new Ramesside line. She was duty, legacy, and calculation—the established choice.

But a young prince’s heart is not governed by strategy alone, and Ramses was being brought up to be stron and independent, to know his own mind and to be a future king. It is highly plausible that amidst this arranged future, Ramses’s eye was caught by another.

Nefertari: Queen, Diplomat, and Confidante

Her name was Nefertari.

She was two years younger than Ramses, and her origins are a blank scroll to us. It is possible that she was also the daughter of a noble house if she had access to the royal court and they were childhood friends that was changing to a different kind of friendship as they entered teenage years. He may have accepted his father’s or mother’s chosen women for his harem, but it is easy to imagine him requesting Nefertari’s presence as his own personal selection.

Nefertari and Isetnofret: Two Pillars of Egypt

Thus, from the very beginning, his private world was balanced between two pillars: Isetnofret, the dynastic spine chosen by his father, and Nefertari, the beloved heart he chose for himself. One was his duty; the other, his reward. The outcome of this arrangement was written in the stone of history: one queen would provide the heirs to secure his throne, the other would capture the soul that would define his legend.

Ramses’ household was a delicate ecosystem of passion, rivalry, and duty. In the harem, a single word — touch — could mark allegiance, intimacy, or warning. He learned to balance love and politics, understanding that both women, as well as his other wives were indispensable to the throne’s stability.

Egypt’s dynasties would see this pattern repeat with other rulers over the millennia.

Ramses world, even as a young teenager, was the crash of swords, the grit of campaign dust, the straightforward strategies of men. Even at 13, Nefertari moved through the crowded, perfumed court in Thebes with a different kind of power. Her name meant “The Most Beautiful of Them All,” but it was a shallow description. Her beauty was not just in her form, but in her grace, in the keen intelligence in her eyes. She didn’t just speak; she listened, her gaze missing nothing.

She had taken his heart. It was a surrender he celebrated. His mother, Queen Tuya, a formidable power in her own right, watched the relationship with a sharp, approving eye. As long as Ramses fulfilled his duty towards his other wives and secured the succession of the dynasty, she had no objection to his favourites. And Nefertari was mindful that she did not arouse animositity in the Queen’s heart. Tuya did not see a rival in Nefertari; she saw a key. She saw the radiant, intelligent mother of future kings, the perfect vessel to secure her son’s dynasty. A silent, powerful pact was forged between these women—one of steel, the other of silk—and Ramesses was the beneficiary of their combined strength.

Isetnofret, in contrast, shared the title of Great Royal Wife with Nefertari but remained in the background, the backbone of the royal house. Her archaeological footprint is faint, yet her children would carry Egypt into the future. She was a principal wife, Great Royal Wife, and mother of a pharaoh. In the quiet halls of the palace, her influence shaped dynastic survival, while Nefertari’s star shone in splendor and ceremony.

History has left her faint, a whisper where Nefertari was a song. But her mark was etched not in stone, but in bloodline. She was the architect of the dynasty’s survival, the steady hand in the quiet halls where the future was truly made.

The Death of Seti I — Bearing the Double Crown

Then came the day – Seti was gone. The mighty restorer, the formidable father, entered the afterlife. The weight of the double crown settled on Ramesses’s brow. The grief was a deep, private well, but from it drew a relentless, burning ambition. He would not just continue his father’s work. He would drown it in magnificence, everywhere except at Abydos. He did not usurp his father’s work with his own – he added to it in Seti’s name. There he built the first or outer courtyard and commemmorated the life and sanctity of his father on those walls in a way that no other pharaoh ever did for another. Ramses clearly left a message for eternity that his father Seti I was beloved of the gods.

The shadow of Seti I was a tangible thing in those early days. It lingered in the cool halls of Thebes, in the weight of the double crown, in the expectant silence that followed the young pharaoh, Ramses II. He was twenty-five, and the throne was his alone. The world, watching, demanded proof.

That proof lay to the north, in the form of a Hittite leviathan coiled around the city of Kadesh.

He rode north not just as a king, but as a father, a teacher. Young as they were, his sons—Amun-her-khepeshef, Pareherwenemef, Meryre—rode with him, their eyes wide, not with boyish wonder, but with the acute fear of men who understand the stakes. He could see his own ambition reflected in them, sharpened by their youth. This was their lesson, written not on papyrus, but on the field of battle.

The Battle of Kadesh — Chaos, Strategy, and Glory

The clash at Kadesh was chaos incarnate. The Hittites, with their thousands of chariots, sprang a trap, shattering his divisions. For a moment, the glorious campaign teetered on the edge of annihilation. History records the Pharaoh’s valor: how he rallied his scattered troops, how he fought like a demon, his chariot a blur of gilded wood and flashing bronze. He carved a legend out of a near-disaster, turning a potential rout into a bloody stalemate.

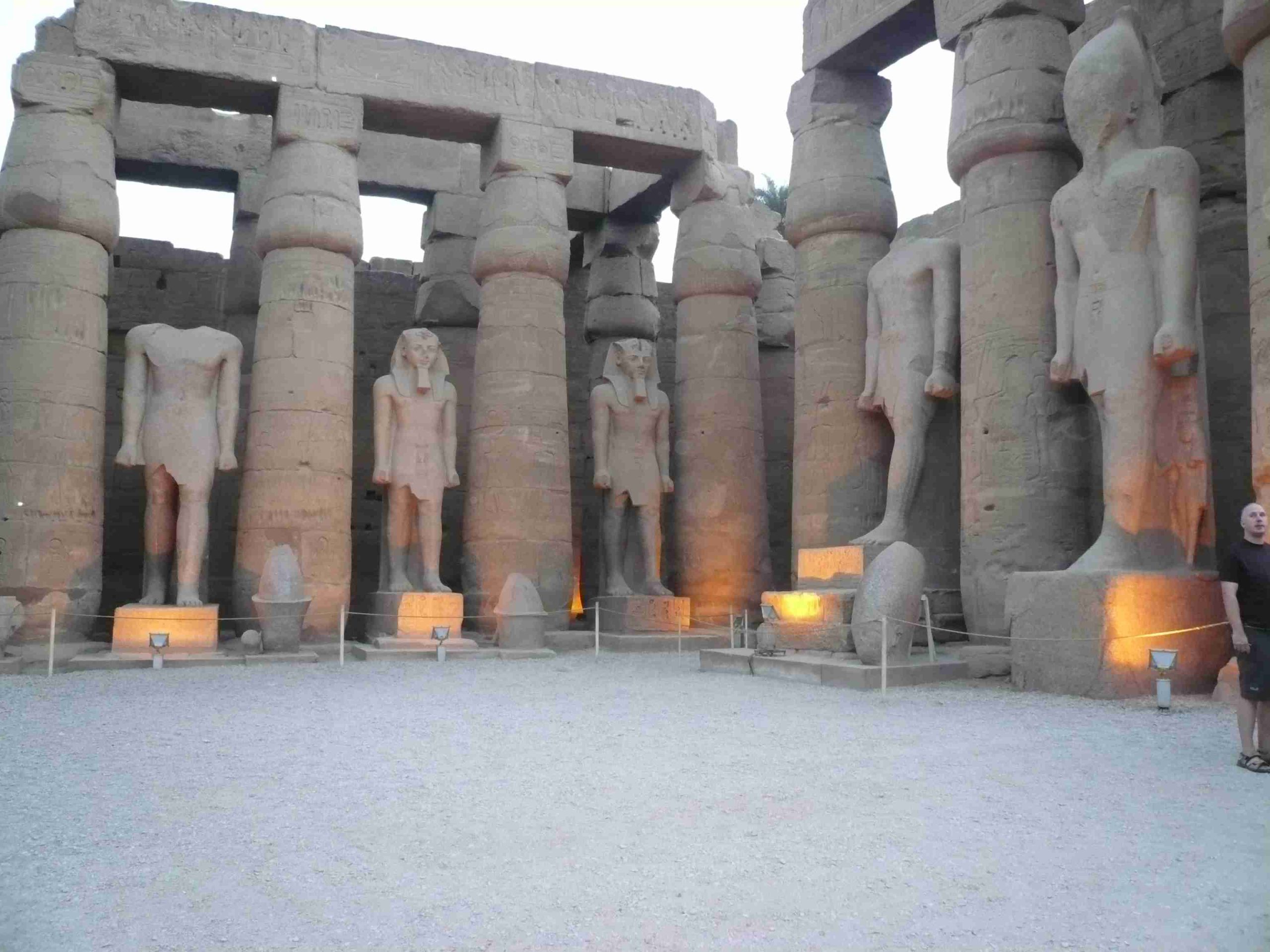

He returned to Egypt from Kadesh not with a conquered city, but with a story. And he told it everywhere. On the towering walls of Karnak and Luxor, on the facade of the Ramesseum, on temples up and down the Nile, the tale was carved in meticulous, glorious detail. There he was, a giant among men, alone against the Hittite horde, his arrows finding their mark while his cowardly army cowered. The reliefs screamed of his divine strength, his strategic genius, his absolute, solitary triumph.

The truth was a more complicated thing, a thing of shattered chariots and negotiated withdrawals. But, the truth is what happens. History is what is written. And in ancient Egypt, the PR spin was as alive as it is today. The victors do not just write history; they get to carve it in stone for eternity. It is a sobering thought: what survives is not the event, but the story told by the one who held the chisel or the pen.

Ramses’ home was his anchor. Nefertari, his heart, her grace a cooling balm after the heat of battle. Isetnofret, his spine, her quiet presence the foundation of his dynasty. In the laughter of his children—the scholarly Khaemwaset, the dignified Meritamen—he found a purpose beyond conquest. They were his true monuments, more lasting than any statue.

In the years that followed, Queen Nefertari was actively involved in Egypt’s diplomatic efforts and was known to have assisted Pharaoh Ramesses II in his foreign interactions, likely communicating with foreign diplomats and queens due to her intelligence and position. While specific recorded interactions are limited, her involvement in government and foreign affairs indicates her role as more than a figurehead.

After Kadesh Ramses II became a storm of activity. Pi-Ramesses, a new capital city, sprang from the Delta mud, a glittering administrative heart for his empire. But Ramses understood something deeper than battle tactics and mere buildings. He understood the architecture of memory, and his true war was against oblivion itself.

And Nefertari was his general in this war. She was his Great Royal Wife, his lover, his confidante, his most trusted diplomat. She gave him his firstborn son, Amunherkhepeshef, and others: Prehirwenemef, Meryatum, the beautiful Meritamen. In a time of crushing infant mortality, each child was a victory, each loss a shared grief that only welded their souls closer together.

Home and Heart — The Private World of the Pharaoh

In the evenings, away from the court, he would find her. He brought her drafts of the poems his scribes were composing for the walls of the tomb he was building for her.

“My love is unique—no one can rival her, for she is the most beautiful woman alive. Just by passing, she has stolen away my heart…” he would read, his voice, usually used for commands, softening.

He would grumble, “It’s not enough. Words are not enough for you. Papyrus decays.”

He called her to his side at court and showed her the plans. Not for a tomb, but for a mountain. Abu Simbel.

Abu Simbel — A Love Letter Carved in Stone

“The Nubians will see it and know our power is absolute,” he said, his finger tracing the drawings of the four colossi that would be his face. “But look here.” His finger moved to the smaller, adjacent temple. “This one is for you.”

The chief architect, a priestly old man steeped in tradition, cleared his throat. “Divine One… the scale… to have the queen’s statues the same height as your own… it is… unprecedented. It breaks the sacred order. The gods—”

“The gods will understand,” Ramesses cut him off, his voice leaving no room for debate. He looked at Nefertari. “She is my balance. My Egypt on the Nile. Her glory is my glory. And so it is!”

The court murmured. The priests were uneasy. To make a queen the equal of the living god was a risk, a defiance of ma’at itself. But Ramesses was unmovable. His love for Nefertari was the one thing more colossal than his ego. This was his greatest act of Heka—the sacred magic that makes words and images into reality. By carving her as his equal in the very stone of a mountain, he was making it an eternal, unchangeable truth. in this world and the next – Ramses devotion to Nefertari was as strong as his father before him, had for the priestess Benetrashit aks Omm Sety (Dorothy Eady) and both understood the power of magic in the spoken and written word.

And so he built. Not just to glorify, but to endure. Pi-Ramesses, a capital city risen from the Delta mud, a beating heart of administration and power. The Ramesseum, with its fallen colossus, a testament to a scale of ambition that bordered on the divine his additions to Karnak and Luxor Temples.

But at Abu Simbel, he built something else. Carving a temple into the face of a Nubian cliff wasn’t just an act of dominion; it was a confession and declaration. There he sits, four times, a god-king staring eternally across his domain. And beside him, not smaller in spirit but equal in devotion, is the temple for Nefertari. It was a love letter in sandstone, a promise that some legacies are built not on the stories of war, but on the quiet, enduring power of love.

Tomb QV66 — Magic and Eternity in Color

But he wasn’t done. While the mountains of Nubia were being hollowed out, his artists were creating her true masterpiece underground. Tomb QV66 in the Valley of the Queens now temporatily open by special ticket.

This was not a tomb; it was a machine of Heka for her resurrection. Every stroke of paint was a spell. The vibrant blues and golds were not mere decoration; they were the very colors of the gods’ realm. She was depicted on the walls, already transformed: playing senet to defeat the forces of chaos, standing before Osiris, being welcomed by Isis and Hathor. This was a magically enforced preview of her future. By depicting it with such exquisite precision, they were ensuring it would happen. The hieroglyphs were not captions; they were incantations from the Book of the Dead, their very shapes possessing the power to protect her spirit, to make her heart light against the feather of truth.

It was his most private, profound gift to her: using the full power of his throne to literally paint her a path to godhood.

Loss, Legacy, and the Children of Ramses II

Yet for all his power, he was powerless before fate. Nefertari died, likely around the 25th year of his reign. The vibrant queen who had corresponded with the Hittite court, the mother of his children, the light of his life, was gone. The court plunged into mourning. For the man who could command the sun, her silence was an agony no monument could soothe.

Their children would be his greatest project, and his deepest sorrow. With Nefertari, his firstborn sons—Amun-her-khepeshef and Pareherwenemef—would rise and fall, their lives cut short. With Isetnofret, the future took a harder, more practical shape: Khaemwaset, the scholar-priest; Merneptah, the steady heir who would inherit an empire in its twilight; and Bintanath, the daughter he would elevate to queen, cementing the bloodline.

He remembered his father’s lesson in the holy silence of Abydos. “Love your queen, my son,” Seti had said, gazing at the carved history of their line. “But it is the children who carry your name. Poets will praise one wife; priests another. But the bloodline is the only thing that outruns the sand.”

Two Voices in His Ear — Legacy and Love Intertwined

This duality would define him. His father’s voice in one ear, a hammer blow of legacy: Build so they remember. His wife’s presence in his heart, a quieter, more compelling force: Build something worth remembering.

He would spend a long life answering both calls. The colossal statues, the grand temples, the spun legend of Kadesh—these were for his father, a defiant shout into the face of eternity. But the smaller, exquisite temple at Abu Simbel, where Nefertari’s statue stands eternally equal to his own? That was for her. That was the quiet, enduring truth of his heart, carved into the living rock so it, too, would never be erased.

Continue the story here Ramses II: From Ozymandias to Abu Simbel’s Sun Miracle

Last updated on 20/12/2025 by Marie Vaughan